22 November 2002

The Quiet American

[finally the movie is released!! they had just finished shooting when i was in HoiAn, Hanoi, and Saigon in the early summer of 2001. and the movie has an 86% score on rotten tomatoes. you can see the trailer here. now playing at Sony Village 7. i can't wait to see it!! -pk]

A Jaded Affair in a Vietnam Already at War

By STEPHEN HOLDEN

http://www.nytimes.com/2002/11/22/movies/22QUIE.html

The mood of wry disillusion that seeps through the screen adaptation of Graham Greene's novel "The Quiet American" is sounded in the movie's opening moments by the voice of Michael Caine musing dreamily on the mystique of Saigon in the early 1950's. It is a place, declares his character, Thomas Fowler, where colors and tastes seem sharper than they do elsewhere and where even the rain has a special intensity. People who go to Saigon in search of something, he suggests in a silky murmur, are likely to find it. That something has everything to do with faraway places and a mirage of sex and adventure in an exotic clime.

Fowler is a wistfully cynical British journalist who has fled an arid marriage in England to live in Southeast Asia, where he is reporting on the Vietnamese fight for independence from French colonial rule. His attitude toward the political turmoil swirling around him is one of studied detachment bordering on disinterest. Only when Fowler is in danger of being summoned back to England does he bestir himself to go into the field and pursue a story juicy enough to keep him at his post.

But beneath his worldly facade lurks a streak of romantic fatalism. Fowler is hopelessly besotted with Phuong (Do Thi Hai Yen), a beautiful former taxi dancer who embodies the Asian feminine stereotype of compliance and impenetrable erotic mystery. Although Phuong lives with Fowler and is financially dependent on him, the relationship can last only as long as he keeps his job. Although he would love nothing more than to take her back to England, his wife adamantly refuses to grant him a divorce.

Fowler may be the richest character of Mr. Caine's screen career. Slipping into his skin with an effortless grace, this great English actor gives a performance of astonishing understatement whose tone wavers delicately between irony and sadness. Fowler is the embodiment of a now-faded British archetype: the suave, impeccably well-mannered man of the world who keeps a stiff upper lip and camouflages any inner torment under a pose of amused knowingness.

Mr. Caine, with his hooded snake eyes and his trace of a Cockney accent, lends Fowler (played by Michael Redgrave in an earlier screen adaptation of the novel) an added frisson of rakish insouciance that makes the character all the more intriguing.

"The Quiet American" is the story of a romantic triangle involving Fowler, Phuong and Alden Pyle (Brendan Fraser), an American intelligence agent operating under the guise of an economic aid worker. Mr. Fraser, looking puffy and wide-eyed, plays Pyle as an earnest, gawky naïf. It is a brave but uncomfortable performance. Even after his character is revealed to be an American spy who speaks fluent Vietnamese, he makes Pyle's lumbering bluntness appear almost comically oafish.

The story begins with Pyle's murder, then flashes back to fill in the whys and wherefores. As the film digs into the characters' relationships, it re-examines the notion that the personal is political in the context of 1950's cold war mentality and the slow fade of the British Empire. Fowler and Pyle's friendship, which rests on quaint notions of gallantry and honor among gentlemen, is also a metaphor for competing styles of imperialism, one wearily resigned, the other aggressively intrusive.

No sooner has Fowler introduced Pyle to Phuong than Pyle falls madly in love with her. Once smitten, Pyle feels no compunction about blurting his feelings about her to Fowler. Pyle's campaign for Phuong has the support of her avaricious older sister Miss Hei (Pham Thi Mai Hoa), who sees him as a bright marital prospect for Phuong.

After Fowler is caught in a desperate lie and Phuong abandons him to live with Pyle, the two men maintain a civilized friendship. Despite their shared passion for the same woman, the movie implies that both view her as a precious toy who can be bartered in a sporting may-the-best-man-win atmosphere. And in the film's most dramatic scene, Pyle saves his rival's life after the two find themselves stranded on the road between Phat Diem and Saigon and take refuge in a French watchtower that is raided by Communist forces.

It could be said that their feelings for Phuong are meant to reflect their countries' different but equally patronizing attitudes toward Indochina. Where Fowler, ever the detached journalist, affects indifference to the Vietnamese struggle, Pyle is a meddling anti-Communist zealot who has no qualms about helping foment resistance to Communist forces by funneling weapons to a ruthless Vietnamese warlord (Quang Hai).

If "The Quiet American" unequivocally views American intervention in Vietnam as an arrogant blunder, the movie, directed by Phillip Noyce from a screenplay by Christopher Hampton and Robert Schenkkan, doesn't convey much strong political passion. Pyle may be buffoonish, but he's not evil. Although a coda to the movie links the events of the story to American prosecution of the Vietnam War a decade later, that afterword seems a convenient formality.

The movie is ultimately more interested in the characters' relationships than in their politics, and it does a superb job of evoking the psychological world of Graham Greene in which the truth of any situation tends to be hidden and riddled with ambiguities. Because "The Quiet American," which opens today in New York and Los Angeles, is told through Fowler's eyes, its drama is muted. More than once violence explodes on the screen, but it seems to come out of the blue in random bursts. Even then, the film conveys little of the excitement or the sense of historical imperatives that drive a movie like "The Year of Living Dangerously."

In burrowing deeply into Fowler's consciousness, however, "The Quiet American" beautifully sustains the mood set by Mr. Caine's opening narration. The world as seen through Fowler's eyes may be a shabby paradise on the verge of ruin. But as he ponders his fate under Japanese lanterns at a riverside cafe in Saigon in the heat of the night, its tawdry glamour exerts a sad but irresistible tug.

"The Quiet American" is rated R (Under 17 requires accompanying parent or adult guardian). It has sexual situations and some violence.

THE QUIET AMERICAN

Directed by Phillip Noyce; written by Robert Schenkkan and Christopher Hampton, based on the novel by Graham Greene; director of photography, Christopher Doyle; edited by John Scott; music by Craig Armstrong; production designer, Roger Ford; produced by William Horberg and Staffan Ahrenberg; released by Miramax Films. Running time: 146 minutes. This film is rated R.

WITH: Michael Caine (Thomas Fowler), Brendan Fraser (Alden Pyle), Do Thi Hai Yen (Phuong), Tzi Ma (Hinh), Robert Stanton (Joe Tunney), Pham Thi Mai Hoa (Miss Hei) and Quong Hai (General Thé).

THE DILETTANTE

THE DILETTANTE: A MODERN TYPE.

from Lyrics of Lowly Life (1896)

by Paul Laurence Dunbar (1872-1906)

HE scribbles some in prose and verse,

And now and then he prints it;

He paints a little,--gathers some

Of Nature's gold and mints it.

He plays a little, sings a song,

Acts tragic roles, or funny;

He does, because his love is strong,

But not, oh, not for money!

He studies almost everything

From social art to science;

A thirsty mind, a flowing spring,

Demand and swift compliance.

He looms above the sordid crowd--

At least through friendly lenses;

While his mamma looks pleased and proud,

And kindly pays expenses.

Shanghai Biennale – Chinese Lucky Estates

Estate secrets

By Winnie Chung

Monday, November 18, 2002

http://totallyhk.scmp.com/thkarts/arts/ZZZ5RUTAI8D.html

THE INHERENT cynicism of Hong Kongers caught South Korean artist/photographer Jung Yeon-doo off guard. Jung had been traipsing around one of Hong Kong's crowded housing estates, asking people if they want a free family portrait. To his surprise, there were few takers for the free 20cmx25cm photo offer.

''I never used to encounter this in Korea, but here [in Hong Kong] I have found people are naturally suspicious,'' Jung says. ''We've put out advertisements in newspapers. The housewives have been interested, but their husbands didn't agree.''

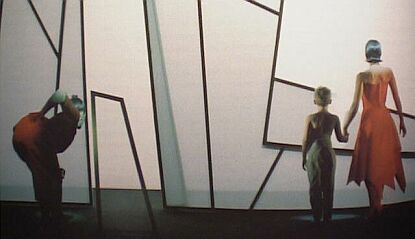

The photographs are part of Jung's exhibition, Evergreen Tower - Chinese Lucky Estates, for the Shanghai Biennale 2002 arts festival, which opens at the Shanghai Art Museum on Friday. The theme for the biennale is Urban Creation, and Jung's work depicting lives within the urban jungle will make a worthy contribution to one of China's most high-profile art events. A preview is being hosted in Hong Kong's 1ASpace art organisation in Cattle Depot Artists' Village, where the portraits are projected on to a wall in a continuous loop.

They are an extension of a similar series Jung produced in South Korea earlier, called Evergreen Tower, in which he took portraits of 34 families in the same apartment block in the city of Kwangju. The idea was to try to offer a glimpse of the lives of the different families through their living conditions and demeanour. Jung chooses apartments with the same layout, and his results show a stage setting capturing the drama of everyday life.

''I want to see behind someone's superficial identity,'' he says. ''Someone can be represented as aged 38, or a father of two, but that doesn't really say anything except perhaps his social status. The photographs will show the audiences what these people are really like through bits of evidence in the photographs. For instance, one family had a huge crucifix on the wall, so we know they are Christians. They chose to pose with musical instruments so you can imagine that they might play for the church choir or music group.''

Jung's project in Hong Kong is sponsored by 1ASpace; he is presently their artist-in-residence. His interest in what lies behind the human facade was his starting point for his current work. Born in South Korea in 1969, Jung studied visual art at Seoul National University before attending Goldsmith's College in London. The self-taught photographer started his artistic career by taking pictures of ballroom and tango dancers. ''It wasn't just pictures of people going through the motions of dance,'' Jung says. ''I liked seeing the emotions behind the dancing; the passion that these people have for this hobby.''

To Jung, art is a kind of voyeurism, but he says it is driven more by curiosity. ''I'm not into obscene voyeurism. This is no different to housewives gossiping about what's happening with a neighbour upstairs or in the next block,'' he says.

Natural cynicism notwithstanding, Hong Kong has been an artistic eye-opener for Jung. His initial idea for Evergreen Tower was to focus on one public housing estate, but he found it impractical after the residents' indifference. Instead, he is now taking pictures of families from different social backgrounds, which means travelling to estates from Tai Po to Sheung Wan or Kwun Tong in any one day.

One foresight he had was to invest in a special wide-angle lens usually used for making movies. ''I was lucky I brought that. Some apartments are so small I cannot even get my camera into them,'' he says, producing his first photograph - one of an old couple living in Tsui Ping Estate in Kwun Tong. ''I had to take that standing outside their door.''

Jung says the more homes into which he is invited, the more interesting his work becomes. ''I'm just curious about how people are living,'' he says. ''I don't want to have to fill in the blanks myself.''

Evergreen Tower - Chinese Lucky Estates forms part of the Shanghai Biennale 2002 festival and runs from November 22 until January 12 at Shanghai Art Museum. The Hong Kong preview is at 1ASpace from Tuesday to Thursday (2pm to 8pm) at Cattle Depot Artists' Village, 63 Ma Tau Kok Road, To Kwa Wan. Tel: 2529 0087

China's Super Kids

China's Super Kids

By NICHOLAS D. KRISTOF

http://www.nytimes.com/2002/11/22/opinion/22KRIS.html

SHANGHAI — Quick, what's 6 + 8 - 7 + 6 + 5?

If you knew instantaneously that the answer is 18, without having to pause even a second, then congratulations! You're as bright as a Shanghai kindergarten student — calculating in his or her third language.

I've met the future, and it is these kids. Americans who come to China tend to be most dazzled by glittering new skyscrapers like the 1,380-foot Jin Mao Tower, but the most awesome aspect of China's modernization is the education that children are getting in the big cities. And the long-run competitive challenge we Americans face from China will have less to do with its skylines, army or industry than with its Super Kids, like Tony Xu.

Tony's real name is Xu Jun, but all the children entering the New Century Kindergarten that he attends get English names as well. Six-year-old Tony's first languages are Mandarin Chinese and Shanghainese, but even in English he rattled off answers to equations faster than I could. It was embarrassing when I posed my own question to him, 10 + 5 - 1 - 4 + 5, and he answered 15 before I could tell if he was right. I want a refund on my college tuition.

Parents pay about $2,000, a huge sum here, to send a child to a year of such a private kindergarten. But since urban Chinese families now have only one child each, no expense is too great for one's "little emperor." Throughout China, first-rate private schools are popping up, as the Chinese saying goes, like bamboo shoots after a spring rain.

Of course Chinese education is still hobbled by rural mud-brick schools that are in a shambles, by peasants who pull their daughters out of school, by third-rate universities. But China's great strength is that in the cities, it increasingly is not a Communist country or a socialist country, but simply an education country.

When I lived in China I represented Harvard in interviewing high school students applying for admission, and it was a humbling experience. The SAT isn't offered in China, so instead the kids take the G.R.E. — meant for people applying to graduate school — and still score in the top percentiles. And while many of my Chinese friends worry that the system works children too hard and costs them their childhood, the brightest kids are not automatons; many are serious enthusiasts of art, music, poetry or, these days, the basketball plays of Yao Ming.

The other day I visited one of Shanghai's best high schools, the No. 2 Secondary School Attached to East China Normal University. American students who have earned a perfect score of twin 800's on the SAT should meet the 17-year-old student here who last year got a perfect score of three 800's on the G.R.E.

He Xiaowen, the principal, showed off 14 gold medals that students have earned in the international math and science Olympics. When I asked if she had any problems with students smoking or drinking, she looked so scandalized that I might have been sent to the principal's office, if I hadn't already been there.

One reason for Chinese educational success emerges from cross-cultural surveys. Americans say that good pupils do well because they're smarter. Chinese say that good students do well because they work harder.

A growing body of evidence suggests that Chinese students do well academically partly because their parents set very high benchmarks, which the children then absorb. Chinese parents demand a great deal, American parents somewhat less, and in each case the students meet expectations.

The result is apparent at No. 2 Secondary School. The students live in dormitories, going home only on weekends, and they're mostly studying from 6:30 a.m. until lights-out at 11 p.m. On Saturdays they attend tutoring classes from 9:40 to 5:10, and on Sundays they do what one girl, Gong Lan, described as six hours of "self-assigned homework."

She explained: "This is extra work to improve ourselves. I read outside books to improve my ability in any subject I feel weak in."

Chinese students may not have a lot of fun, and may lag in subjects in which some American students excel, such as sex, drugs and rock 'n' roll. But these kids know their calculus and are driven by a work ethic and thirst for education that make them indomitable. With them in the pipeline and little kindergartners like Tony Xu behind them, China may eventually lead the world again.

A new dawn in China for VC?

A new dawn in China?

by Rebecca Fannin Posted 02:40 EST, 21, Nov 2002

http://www.thedeal.com/

Near the bustling city of Shanghai in the high-tech center of Pudong, a semiconductor foundry is churning out silicon wafers for China's fast-growing electronics market. Far from the world's financial capitals, Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corp. represents the dreams of international venture capitalists doing deals in the one of the toughest places to make money — China.

In a conference room in the ultramodern facility, Richard Chang, president and CEO of the plant, says he expects it will be profitable by the end of the year. SMIC's chips are not as advanced as those produced in Taiwan, he explains, but the company is targeting the less technologically sophisticated domestic Chinese market, which is growing by 25% yearly.

SMIC will go public in New York or Hong Kong by the second quarter of 2004, predicts Chang, who was recruited from Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. With the IPO, he predicts, the company's venture backers, H&Q Asia Pacific, Walden International and Vertex Management as well as Goldman, Sachs & Co., should make at least two to four times their original investment of $1.1 billion.

Cut to Beijing: A Starbucks near the Forbidden City is selling moon cakes for the annual Harvest Moon Festival and is packed with locals who can afford to pay Rmb9 ($1.09) for a cup of brew. It, too, has venture capitalists salivating over possible returns.

When H&QAP exits its investment in the 30-store, Beijing-based Starbucks franchise it hopes to gain "quite a good return," says Ta-lin Hsu, chairman of the Palo Alto, Calif.-based Asian venture capital firm.

In 1998 H&QAP invested $10 million to acquire a controlling stake in Mei Da, the licensee for Starbucks in Beijing and nearby Tianjin. The franchise became profitable this summer and revenues are growing at a double-digit rate, says David Sun, president of the Beijing operation, which is adding 10 stores per year to meet demand and prepare for the 2008 Olympic Games. Sun likens the progress of Starbucks in China to the expansion of McDonald's across Taiwan in the 1980s, which he helped spearhead. H&QAP hopes to exit through a sale, an IPO or by exercising a put option with Starbucks Coffee Co., though it has no target date yet.

Such promising investments symbolize a change in China, where successful venture investing stories have been rare. Many venture capitalists took a bath on their investments from the early 1990s.

Most of the early deals were joint ventures with or investments in government entities, which rarely paid off. Bureaucratic labyrinths, entrepreneur con men and widespread corruption compounded matters. And when an investment did pan out, it was hard to get profits out of the country.

But there are signs that VCs have learned their lessons, and even the hardened veterans sound optimistic that recent investments have avoided the pitfalls of the past.

"China is the one bright spot in the world," says Lip-Bu Tan, chairman of the Palo Alto, Calif.-based Asian venture firm Walden International, citing the country's GDP growth rate of 7% to 8% in contrast to the stagnant European and sluggish U.S. economies. "It's not just hype and hope."

Last year, VC investment in China doubled to $1.75 billion, according to the Asian Venture Capital Journal in Hong Kong, while overall investment in Asia declined 3% to $11.9 billion.

Other factors should also give VCs a boost, Tan says. "You have the Olympics coming, [World Trade Organization membership] and you have growth from a very low base." In addition, he adds, there is a "tremendous talent pool of engineers with Ph.D.s" who are keen to start businesses.

Recent changes to rules governing foreign-owned ventures should make it easier to repatriate profits, too.

"What's happening in China now is very much like what happened to Silicon Valley in the 1970s when there was a surge of entrepreneurial activity," says Len Baker, a partner at Palo Alto, Calif. venture capital firm Sutter Hill Ventures. His firm put up an initial $6.5 million to help back the $55 million fund raised by Shanghai-based Chengwei Ventures LLC, which also boasts Yale University as an investor.

The VC community has developed enough now that 38 firms, including Warburg Pincus and Newbridge Capital Inc., recently set up the China Venture Capital Association to lobby for more favorable government regulations and instill ethical and professional industry standards.

Institutional investors have taken note, too. A conference on Chinese venture investments sponsored by Chengwei in Shanghai in September drew Georganne Perkins, director of private equity at the $8 billion endowment run by Stanford Management Co., and Clinton Harris, managing partner of Grove Street Advisors, which manages venture capital investments for the $135 billion California Public Employees' Retirement System.

Still, investing in China isn't easy. To begin with, due diligence is prolonged because of the danger of fraud. Tan, who has completed 23 deals in China since 1994, has been stung by managers who either took bribes or pocketed some earnings. "For them, it might be an accepted way of doing business in China, but for us, it is a no-no and we want out of those deals," says Tan.

Regulations and red tape plague investors in China, but there are a few signs of progress. China now permits foreign-owned VC funds denominated in Chinese renminbi. Foreigners continue to establish offshore holding companies or foreign investment enterprises to invest in China, because those entities can be listed outside China, making it easier for investors or realize profits in hard currencies.

Some sort of offshore structure had been necessary because IPOs within China don't provide a viable exit for foreign investors, explains Chang Sun, managing director at Warburg Pincus Asia LLC in Hong Kong. Domestic IPOs require a long and complicated approval process and don't provide liquidity because founding shareholders are prohibited from selling shares for three years after the listing; only newly issued shares in the IPO can be sold. The same rules apply to H shares, the shares of a Chinese company listed on the Hong Kong stock exchange. There are also restrictions on red chips, companies incorporated and listed in Hong Kong with controlling Chinese shareholders.

Despite all the handicaps, funds like Walden are looking for new companies. Tan, a Malaysian-Chinese who grew up in Singapore, shuttles back and forth between California and China about eight times a year looking for new investments and checking on his portfolio. Over the past year, he has added four staffers in China, bringing the team to 12.

Over the next three years, he plans to invest a further $150 million to $200 million of the firm's $750 million fund in China — more than any country in Asia. Most of that will go to startups in software, telecom and semiconductors — areas that are benefiting as China modernizes.

Tan has learned some lessons since his early days, though. This time, he only wants to back firms that are founded by Chinese-born, American-educated entrepreneurs who are returning home to start businesses. This strategy helps solve one of the biggest hurdles in investing in Chinese companies: finding capable managers.

So far, this approach has produced one very profitable investment. In a trade sale in April 2001, Tan made $18 million on a $4 million minority investment in a firm founded by a "returnee," Ying Shum of New Wave Semiconductor. The firm was sold for $80 million to Silicon Valley-based Integrated Device Technology Inc., Walden's most successful deal to date.

"We learned from our mistakes and have decided not to do any more JVs or state enterprises," says Tan. Joint ventures didn't make Walden any money. Deals with state-owned entities produced 1.6 to 1.8 times the initial investment, he says.

"We have not had any write-offs in China yet," he says. But 12 of the 23 companies acquired by the 1994 fund remain there. "We are struggling with a few and are trying to redeem some shares by having them buy us out," he concedes.

Similarly, H&QAP didn't suffer as much as some others, says Hsu, a godfather of Asian venture capital who helped to jumpstart Taiwan's technology industry during the 1970s.

All told, he has invested about $200 million in 15 Chinese deals from its initial China fund and from a regional fund.

"We didn't lose our shirts" says Hsu.

But past deals, which date to 1993, have yielded returns of only about 1.2 to 1.3 times his investments, he says, and there have only been three or four exits — including two real estate projects plus Hainan Airlines Co. Ltd. Those have allowed him to return most of his investors' capital, however.

"We have not written off anything," he says. "We just do not give up."

While Hsu bears the scars from early investments, he has had fortune on his side, too. Last year, he says his firm was able to "get its equity out of" two $10 million to $12 million real estate investments in Dalian and Shenyang as the real estate market recovered from a 1996-2000 slump.

Within the next year, Hsu says he will take Yan Sha, a large and profitable Beijing-based department store franchise, public on a Chinese stock market or sell it to co-investors, the Friendship Store and Hendersen Land.

Hsu says he is in negotiations to sell a portion of Shenzhen-based Sinogen International Ltd., the largest pharmaceutical manufacturer in China, to a U.S. investor "at a pretty good valuation." But he's unlikely to see a big profit on the company, which produces human growth hormone and insulin for the Chinese market. Returns would have been "two to four" times H&QAP's $25 million to $30 million investment seven years ago, he says — if things had gone according to plan and Sinogen had gone public in China two years ago.

He's optimistic, though, about a successful exit from the $12 million investment he made four years ago in Grace THW Group, a producer of fiberglass cloth for printed circuit boards. Grace is run and backed by Winston Wong, the son of Taiwan's top tycoon, Wang Yung-ching, the president of Formosa Plastics Corp., and Jiang Mianheng, son of Chinese President Jiang Zemin. Hsu says Grace will go public toward the end of next year.

So far, the successful exits cited by the VCs have mainly been late-stage technology companies or real estate deals — not early-stage companies. So it remains to be seen how the latest wave of investments in those kinds of companies will turn out.

At Chengwei, most of the nine portfolio companies — mostly early-stage technology companies — are not showing profits yet, partner Bo Feng says, and some don't even yet have revenue.

The danger, he warns, is that with so many venture capitalists scouting for deals, China "is becoming overheated."

Given the checkered record of foreign investors there, he's probably right to be cautious.

Out of work bankers go freelance

Out of work bankers go freelance

by Heidi Moore Posted 02:44 EST, 21, Nov 2002

http://www.thedeal.com

When Robertson Stephens collapsed in July, one head of mergers and acquisitions for a midsize bank looked into hiring a few of the displaced bankers. With a solid name behind them, good contacts and a small pipeline of deals to support them, the Robbie team would be a good investment, he thought.

The only problem: he couldn't afford to pay them. So he devised a plan under which the bankers would work on an "eat what you kill basis." Under this scenario, the bankers get both a finder's fee and a portion of the retainer for any deals they brought in — a cut that could equal up to 20% of the final value of the deal.

You've heard of freelance writers and freelance consultants. Make room for freelance bankers.

As Wall Street continues to lay off employees, freelancing provides a way for displaced bankers to remain in the business without finding a permanent job. And it allows cost-conscious investment banks to acquire talent in a relatively inexpensive way.

"I suspect anyone looking to hire in this market would do it on that basis," said Rohit Manosh, a former Lehman Brothers Inc. banker who helped found merchant bank Tri-Artisan Partners in April. "In the past you haven't gotten good people that way, because they had other options, but for the first time you have very few options out there."

But freelancing is hardly a cure-all for out-of-work bankers or firms that hire them. For one thing, it is difficult for a bank to build a team environment when some of its bankers are really working for themselves, says Jon Melzer, a managing director charged with expanding the M&A practice at boutique Houlihan Lokey Howard & Zukin.

"If you have that type of model, it becomes a free-agent culture, which is not so bad except that you can't control the quality as much," Manosh adds.

It can also be difficult for banks, especially the largest ones, to trace the fees from a particular deal back to a specific person.

Still, some firms have embraced the freelance banker formula.

"It seems to me to be a convenient thing given the current times, where there are some fellows who have some dealflow they want to keep working on, but the firms are all cutting salaried staff," says Fred Joseph, co-head of investment banking for Morgan Joseph & Co. Joseph says he compares the practice to that of law firms who bring on lawyers as "of counsel."

Joseph says the strategy has had "varied success," but to accommodate its unpredictability, his firm often pays bankers on a sliding scale. Freelancers get a certain percentage of the deal fees if they haul the entire workload; they get 50% of that percentage if the firm has to provide a lot of support staff, 25% if the banker only brings in the client relationship and leaves the nitty-gritty to associates.

Several dealmakers noted that the impetus for freelancing comes most often from bankers looking for work, rather than the firms themselves. The impulse is simple, says Cynthia Remec, president of investment-banking executive-coaching firm Cynthia Remec Associates: "The opportunity cost is infinitesimal," Remec notes. "If they didn't do this, the odds are they wouldn't be working now anyway."

Remec says the trend has not just encompassed senior bankers, like managing directors, but has also trickled down to young bankers, who are even offering to work for free for start-up boutiques to pick up experience. For better established smaller banks, they are offering to work on a week-by-week basis, Remec says.

Either way, it's a tremendous change from the base plus bonus pay packages young and midlevel bankers are used to, but can no longer count on receiving. Some are finding that they can't even give their services away. One head of M&A for a large bank said that, although he has been approached by young bankers looking to work for free, he would never hire them, primarily because of the slave labor aspect.

"It's terrible," he says. "If they do a great job, you can't pay them so you feel bad. If they do a horrible job, they still put in the effort, and you still can't pay them so you feel bad." He adds that at a large bank, it would cause too much resentment to have one young banker do the same work as his or her colleagues, but get paid nothing.

And, Joseph notes, there is one non-negotiable element to picking freelance hires: "The firm takes on real regulatory and supervisory obligations, so you need to know the guys who are taking on your aegis," Joseph says "But if [a hire] really does have dealflow, it can be profitable for both of you."

21 November 2002

THE POET AND HIS SONG

THE POET AND HIS SONG

from Lyrics of Lowly Life (1896)

by Paul Laurence Dunbar (1872-1906)

A SONG is but a little thing,

And yet what joy it is to sing!

In hours of toil it gives me zest,

And when at eve I long for rest;

When cows come home along the bars,

And in the fold I hear the bell,

As Night, the shepherd, herds his stars,

I sing my song, and all is well.

There are no ears to hear my lays,

No lips to lift a word of praise;

But still, with faith unfaltering,

I live and laugh and love and sing.

What matters yon unheeding throng?

They cannot feel my spirit's spell,

Since life is sweet and love is long,

I sing my song, and all is well.

My days are never days of ease;

I till my ground and prune my trees.

When ripened gold is all the plain,

I put my sickle to the grain.

I labor hard, and toil and sweat,

While others dream within the dell;

But even while my brow is wet,

I sing my song, and all is well.

Sometimes the sun, unkindly hot,

My garden makes a desert spot;

Sometimes a blight upon the tree

Takes all my fruit away from me;

And then with throes of bitter pain

Rebellious passions rise and swell;

But--life is more than fruit or grain,

And so I sing, and all is well.

20 November 2002

And So To Bed

And So To Bed

Issue cover-dated November 28, 2002

By Brian Mertens/BANGKOK

http://www.feer.com/articles/2002/0211_28/p064current.html

WITH THE GOVERNMENT cracking down on nightlife excesses, trendy young Thais have decided there's only one thing to do: Take it lying down. And so they're heading straight to the Bed Supperclub, an upmarket bar and restaurant in Bangkok where lounge lizards dine while sprawling on giant divans.

Viewed from the street, the Bed is a huge, elliptical metal tube that seems to have landed like a spaceship amid the noodle carts and massage parlours off Sukhumvit Road. "It's intended to look alien, like a cocoon or a temporary structure, as if you could pick it up and take it somewhere else," says the project's Australian-born designer, Simon Drogemuller, of Bangkok's Orbit Design consultancy.

Inside, things get even more intriguing. The gleaming white interiors are reminiscent of something from Star Trek or 2001: A Space Odyssey. Staff ritually plump the big white pillows and smooth the 15-metre-long sheets that cover the divans lining the walls. The curved walls glow with colours projected by digital light-organs, or dance with images from a video installation commissioned from Thai artist Kamol Phaosavasdi. (The Bed plans more exhibitions and live music gigs.)

It might all sound a bit extreme, but the Bed is actually a pleasant place to visit. The atmosphere is light and bright, and the music is kept low, at least by Bangkok standards. The food's not bad either, and not out of orbit for a high-end Bangkok nightspot--$16 fetches three courses of fusion cuisine. Recent highlights included a black-mushroom consommé with goat-cheese cream and garlic-roast chicken breast on almond-tomato salsa with spicy basil vinaigrette (avoid the fennel and black-olive risotto, though).

Opened in October, the venue is already a hit with Bangkok's design crowd, media people and high society, as well as visitors like Keanu Reeves and Julia Roberts. "It's a fantasy setting, like opening the pages of a good fashion magazine, a dreamland you thought you could never enter," gushes one visitor, fashion writer Watcharin Phongsai. "You can just pop down and feel like you're in an MTV video."

The downside? Well, as diligent loungers might point out, the Bed is not the first venue in the world to let its guests stretch out on divans. Indeed, Drogemuller, readily concedes that Amsterdam's Supperclub got there first. Still, there's nowhere else quite like it in Thailand.

"We thought it would work because it's unique," says Drogemuller. "Dining on beds is closely associated with the middle-to-high-income people who go to these sorts of places. You get the feeling you are being treated like a king."

BED SUPPERCLUB

26 Sukhumvit Soi 11, Sukhumvit Road, Bangkok

Tel.: 651 3537

Fashion's High Priestess of Gnosticism

Fashion's High Priestess of Gnosticism

By HERBERT MUSCHAMP

http://www.nytimes.com/2002/11/17/fashion/17VIEW.html

Why don't you . . . give all your ideas away to other people, so that you'll fill up again with new ones? Diana Vreeland, the great fashion editor, understood that this is how creative minds work. It's fatal to be a hoarder. When you have an idea, get it out there. Pretend you're Josephine Baker, tossing fruit into the audience. Hit someone on the head with a pineapple. Circulate the energy. Distribute the wealth. Rinse your child's hair with dead Champagne.

This is a gnostic way of thinking. Now relax. It's Sunday. You won't mind a bit of Gnosticism with your Styles. Glamour and knowledge both share the same root in gnosis (secret learning), so why shouldn't Gnosticism be fashion's true faith?

The gnostics were a religious order, circa the year 0, but in modern times it makes better sense to view them as a personality type. Vreeland was one of them.

"If you do not bring bring forth what is within you," the gnostics believed, "what you do not bring forth will destroy you." And I suspect Vreeland truly believed that if she had an idea and didn't get it out there, it would kill her. Killer-diller. If she couldn't come out with observations like "pink is the navy blue of India," she would die.

Thanks in part to those observations, she hasn't. Or, rather, the point of view defined by Vreeland's insights remains indispensable. It is the viewpoint of fearlessness, the stance of "Why not?" And if Vreeland's legend looms larger today than it did during her lifetime, that may be because this particular stance has become harder to sustain.

Vreeland is the subject of a new biography by Eleanor Dwight, and it is the first to explore the personality behind the histrionic public persona. The book rides a wave of printed material by and about Vreeland that did not begin until years after her retirement from Vogue. "Allure," a coffee-table book, written with Christopher Hemphill, of black and white photographs punctuated with Vreeland's taped recollections of them, was published in 1980 and has been reissued this year.

The first book was followed in 1984 by the editor's memoir, "DV." Two additional volumes of Vreeland's musings have appeared in the last year: "Why Don't You?" a collection of her columns for Harper's Bazaar, and "Vreeland Memos," an issue of the fashion periodical Visionaire.

Why don't you . . . buy Dwight's biography and read it, so that I don't have to try your patience with one of those super-compressed summaries that nobody reads anyhow? "Elegance is refusal," Vreeland once pronounced. I don't know whether this is a gnostic idea precisely. But it appears to be an essential antidote to excessive gnostic fecundity. If what you have to bring forth is tedious, just leave it alone.

Vogue in the 1960's was as much the creature of its time as it was the creation of an editor. At the beginning of the decade, fashion magazines reflected a relatively rarefied realm of elegance, style and social poise. Ten years later, they had become a mass medium. Vreeland's Vogue occupied the pivotal place in this transformation. Herself a latter-day Edwardian Woman of Style, she hit her manic professional stride in the postwar years, when people were just beginning to grasp the full extent of changes brought about by mass communications.

These circumstances are unrepeatable. That's why it is pointless to complain that no magazine quite like Vreeland's exists today. No world like hers exists today. When she started out, celebrity was tantamount to notoriety. Now, the news media are glamorous in their own right. Today, everybody knows who Diana Vreeland was. In her own time, she communicated to audiences who never gave much thought to who an editor was.

I know, because I was part of it. When I started reading Vogue in my early teenage years, I had little interest in fashion and knew even less about it. Rather, like The New Yorker, and Ada Louise Huxtable's architecture columns, Vogue represented what I recognized as an urban point of view. I found my suburban life confining. It was a relief to project myself into the escapist fantasies offered by those texts. I wouldn't know of the existence of Diana Vreeland or William Shawn, the editor of The New Yorker, until many years later. Now the situation has changed. We're all regaled by the antics of editors without magazines.

Vreeland, I later read in a biography of Alexander Lieberman by Calvin Tomkins and Dodie Kazanjian, once described Vogue as "the myth of the next reality." The myth was accurate in my case. The next reality was relatively exempt from the pleasures of cold war normalcy.

People were onto something when they called Vreeland the high priestess of fashion. She was a gnostic priestess. In the gnostic system, there was an outer mystery for the many and an inner mystery for the few. So it was with Vreeland's Vogue. Many readers may have regarded it as the leading fashion magazine. Others, too few to constitute a mass readership, understood that glamour has only incidentally to do with clothes. It has mainly to do with personality structure, with the places we choose to dwell or avoid within the architecture of our subconscious fantasies.

Now, the point of Gnosticism is to be reborn to the divine within oneself. If "the divine" is not acceptable, you can substitute the truth within oneself. Or, as the psychotherapist D. W. Winnicott called it, the authentic self. But Vreeland probably would be comfortable with the divine.

Why don't you bring out that divine thing that is within you? If you don't, that divine thing will slay you.

In any case, you have to kill off the inauthentic, or at least not let it take over the executive committee of the self. Vreeland was vigilant in this regard. Of course, she was also a fabulist. She made up or grossly exaggerated her accounts of her past and the world around her. But if she had stuck to the facts, she would have falsified her self. She had "the wound" of the creative artist: an unshakeable disbelief in her potential to be loved, coupled with an iron determination to conceal this disbelief from herself. From this stemmed her power as an architect of other people's desires.

Ms. Dwight's biography is, among many other marvels, a brilliant study in the relationship between love and work. The book is a treatise of changing mores, too, of course, but at heart it is a report from the front lines in the struggle to craft new identities for men and women in the modern world of work. The evidence suggests that Vreeland was not a feminist. She was, however, a strong woman and a breadwinner who reformed the decorous world of fashion magazines within her muscular grip.

Vreeland's is the flip side of the "Lady in the Dark" story. This extraordinary woman blossomed when circumstances forced her to create a world outside her marriage to a man of limited emotional and financial resources. Reed Vreeland looked the part of leisured money. The leisure part was real. He was a Ralph Lauren ad campaign before a Ralph Lauren was even dreamed of, but evidently possessed neither the earning power nor the work ethic of an average male model. A woman who considered herself unattractive might see him as a catch.

But what a lot of hard work it must have taken for Vreeland to believe that he was worthy of her devotion! The fantasies it must have taken to fill up the vacuum between herself and a human version of the spotted-elk-hide trunks she advised her readers at Harper's Bazaar to strap on the backs of their touring cars! She was herself the driver. And although it is pleasing in life to travel with attractive luggage, greater rewards await those who travel light. A higher quality of attention will be paid to the active partner in the wider world.

"I know what they're going to wear before they wear it, eat before they eat it, say before they say it, think before they think it, and go before they go there!" This astonishing outburst, once overheard by Richard Avedon, could be taken as evidence of a fashion dictator's disrespect for her readers. But perhaps the woman was simply reassuring herself that she could trust her instincts.

What else did she have to go on? It's not as if she was dealing with anything rational. In "DV," Vreeland recounts the possibly apocryphal story of assigning a photographer to shoot a picture against a green background. The photographer strikes out after three attempts. " `I asked for billiard table green!' I am supposed to have said. `But this is a billiard table, Mrs. Vreeland,' the photographer said. `My dear,' I apparently said, `I meant the idea of billiard table green, not a billiard table.' "

In other words it did not pay to follow this dictator literally. Far better to respond with instincts of one's own. This, I think, was the core clause in Vreeland's contract with her readers. We expected her to know where we were going before we went there. We were traveling to places deeper within ourselves.

LBOs: Embracing Barbarians at the Gate

LBOs: Embracing Barbarians at the Gate

Beaten-up companies looking to go private are seeking buyout firms

By Emily Thornton in New York, with Stephanie Anderson Forest in Dallas

http://www.businessweek.com

Henry R. Kravis is like a kid in a candy store. Three years into the worst bear market since 1929, the legendary dealmaker is buying companies left and right. Since June, his firm, Kohlberg Kravis Roberts & Co., has announced plans to acquire businesses worth about $7.5 billion. They include a Canadian phone directory publisher and a French electrical equipment maker. Besides, KKR is eyeing hundreds of American companies. "We're busy again. I love it," Kravis says.

The buyout kings are back. Not since the 1980s have the pickings been so rich for leveraged buyout firms like KKR in the high-profit, high-risk business of buying, fixing, and reselling companies. Sidelined throughout much of the late 1990s, when merger mania pushed asset prices out of sight, they are now picking up businesses at bargain prices as companies shed what they couldn't digest. Flush with more than $100 billion raised from the likes of pension funds, they're emerging as a powerful force in a new wave of restructuring.

This year, LBO deals have soared. Between January and Nov. 6, they were up 50% vs. the same period a year ago to $20 billion--three-fourths of that rise was in the third quarter when they accounted for almost 10% of all mergers and acquisitions announced. That's their largest share since 1989. By contrast, overall M&A activity shrank 57% to $379 billion.

Given their vastly increased financial clout, the LBO firms will be key players in refocusing companies on making better use of their capital instead of chasing growth at all costs. "LBO firms will play a substantially more important role in the current corporate transformation than they did in the 1980s," predicts Alan K. Jones, a managing director and co-head of the group that advises buyout funds at Morgan Stanley. "This is their renaissance."

It's not just low prices that are bringing buyout kings out of the woodwork. It's their conviction that they're in the sweet spot. They believe prices are not going to fall much further. At the same time, there's little risk that chastened companies will bid up prices. "With so many strategic buyers on the sidelines, the environment strongly favors financial buyers," says Sean O. Mahoney, a managing director at Goldman, Sachs & Co. who specializes in LBO financing.

Buyout firms are snapping up hot properties in industries with stable cash flow. Initially, they have focused on yellow-pages publishers, fast-food chains, and book publishers such as Boston's Houghton Mifflin Co. But they're expected to branch out across the economy, as distressed companies like Qwest Communications International (Q ), WorldCom, Vivendi Universal International (V ), and Nortel Networks (NT ) shed more assets.

In many respects what's happening is an about-face from the 1980s, when some buyout funds were the pariahs of the financial world--Barbarians at the Gate, as one book dubbed them. Back then, a handful of firms used mountains of debt to buy public companies in hotly contested deals, took them private, then ruthlessly cut costs to make them profitable.

This time around, LBO shops are invited guests. Sellers are thrilled to do deals with them. Managers consider the stock market more punishing than going private under a new owner. Many also see LBOs as their best chance to motivate managers whose options are under water. Once a company is taken private, buyout firms can shower managers with fresh options at dirt-cheap prices that they can cash in when the company is sold. "Our buyouts are management-led," says William E. Conway Jr., a co-founder of the 15-year-old Carlyle Group. "Hostile takeovers are a thing of the past."

But it's not going to be as easy for LBO firms to extract profits from their prizes. Their slash-and-burn methods are now standard management procedure, so there's less fat to cut. "Our job is a lot harder today because companies are better run," says Perry Golkin, a member of KKR. Adds Harold W. Bogle, a managing director at Credit Suisse First Boston: "You have to look to grow in more strategic ways."

That's why many buyout firms are rolling up their sleeves and getting involved in running the companies they buy. For example, Texas Pacific Group partners made sales calls on the top 15 customers of silicon wafer maker MEMC Electronic Materials Inc. (WFR ) to convince them the company was financially sound. "Firms will be substantially more hands-on than they historically have been," says James G. Coulter, a founding partner at Texas Pacific.

The pressure on firms to deliver returns may even spark another flurry of mergers--this time between the companies in buyout firms' portfolios. "You may see more financial buyers selling to financial buyers," says Carlyle's Conway. They may drive a hard bargain, though. In the mid-1990s, says Mark L. Sirower, head of the M&A practice of The Boston Consulting Group, corporate buyers on average lost 5% of what they paid for businesses, while LBO firms made roughly 25%. The superior returns show how closely major buyout funds scrutinize their deals. On average, they pick only one out of 100 they consider. "The difference is that corporations often acquire to be bigger. LBO firms acquire companies to make money," Sirower says.

Not that the LBO firms always get it right. Many are still nursing their wounds after straying from cheap, understandable businesses at the peak of the market. In 2000, LBO firms did $40 billion of deals after many lost patience waiting for the stock market to decline and took ill-fated gambles. Big firms--including Forstmann Little & Co. and Hicks, Muse, Tate & Furst Inc.--together lost billions of dollars on telecom investments made around that time. "I guess we could have all taken a year off and played golf, which would have been a great idea in hindsight," says Thomas O. Hicks, co-founder of Hicks Muse.

This bitter experience is making buyout firms a lot more cautious. Many are forming consortia to share the pain if deals go sour. On Oct. 31, four buyout shops--Thomas H. Lee Partners, the Blackstone Group, Bain Capital, and Apax Partners--said they teamed up to buy Houghton Mifflin from Vivendi.

This newfound caution sits well with today's LBO investors. More public pension funds are backing buyout firms than in the 1980s, and they face heightened scrutiny of their own investments. For example, the University of Texas Investment Management Co. (UTIMCO) recently decided to release its LBO returns on request--breaking a taboo for the secretive firms. "The board felt with the changes that had taken place in the overall environment, we would have to move to a higher level of disclosure," explains Bob Boldt, president of UTIMCO.

The less forgiving business climate presents other obstacles. For starters, bond investors to whom the LBO firms turn for debt financing are getting wary of big deals. And, because many of the companies for sale face shareholder lawsuits and investigations, it's becoming more complicated to close deals on schedule. For instance, the news on Nov. 4 that Vivendi's financial disclosures are under investigation by U.S. and French authorities could thwart the Houghton Mifflin deal. "I'm sure that is complicating the effort to close a sale," says Jonathan Newcomb, former CEO of Simon & Schuster Inc. and now a principal at private-equity firm Leeds Weld & Co.

For now, the buyout kings aren't too worried. They're giddy over the great American fire sale. Plenty more cheap merchandise will hit the racks. "We always thrive when there is turmoil in the markets, and God knows we have turmoil," says Kravis. When the going gets tough, the tough go shopping.

U.N. Revives Plan for Khmer Rouge Trial

After 9-Month Break, U.N. Revives Plan for Khmer Rouge Trial

By ELIZABETH BECKER

http://www.nytimes.com/2002/11/21/international/asia/21CAMB.html

After nine months, the United Nations revived plans yesterday for an international trial for the surviving leaders of the Khmer Rouge. They are charged with genocide and gross human rights violations in the deaths of more than one million Cambodians in the 1970's.

But the resolution that ultimately passed in a key committee had been watered down to meet Cambodia's approval.

Although it calls for resuming negotiations on creating a special crimes tribunal, it requires that such a tribunal adhere to 2 of the 53 articles of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

The measure also notes with approval a new Cambodian law that insists that Cambodia's ill-trained and corrupt courts have the final say in the proceedings, rather than the United Nations.

Sponsored by Japan and France, the measure passed the committee unanimously, with more than 100 voting for it 37 abstaining. It still faces a General Assembly vote, but is expected to pass.

It was immediately criticized by several diplomats and rights advocates for failing to ensure that the trial would meet adequate international standards for fairness.

"The resolution fails to include explicit language guaranteeing the tribunal will meet international standards, and it lacks a solid commitment from the Cambodians," said a senior diplomat whose country nevertheless voted for it.

After four years of talks on a tribunal with Prime Minister Hun Sen's government, such complaints have become familiar. In February, deadlocks and disappointments over the tribunal led the United Nations to announce that the talks had stopped.

Nations led by Australia, France, Japan and the United States worked to start another effort. Cambodia is one of relatively few countries to suffer such devastation since World War II without seeing those who carried out the actions brought to trial — despite the 23 years that have elapsed since the Khmer Rouge were overthrown. In that time, there have been trials or truth commissions for Rwanda, Sierra Leone, South Africa and the former Yugoslavia.

Secretary General Kofi Annan reconsidered. In August, he said he would resume talks if given a "clear mandate."

The new resolution was intended to provide that mandate, but even its original sponsors disagreed over whether it was strong enough to ensure fairness.

Australia withdrew its sponsorship at the last minute, when Cambodia called for changes. "We found the changes to weaken the text, but we were not prepared to vote against it," said Ambassador John Dauth of Australia.

Scholars and rights experts said they feared that with so many governments eager to redress an omission, there had been more willingness to water down international law to win Cambodian approval.

"This resolution does not even ask the Cambodian government to live up to the very minimum international standard for a fair trial, much less build in guarantees that those standards will be adhered to," said Stephen R. Heder, a Cambodia scholar at the University of London.

Prime Minister Hun Sen, a minor Khmer Rouge military officer in the first years of the killings, engaged in drawn-out talks with the United Nations. Under his direction, Parliament passed a law to set up a tribunal. The measure had provisions unacceptable to the United Nations.

Michael Kors & Uptown Guys

[old but nice article on Michael Kors...]

Uptown Guys

By Amy Larocca, New York Magazine - August 12, 2002

http://www.newyorkmetro.com/nymetro/shopping/fashion/6277/index.html

His classic, luxurious aesthetic has made Michael Kors the go-to designer for society girls. Now he's setting his sights on the well-dressed lady's most important accessory: her man.

Michael Kors is not the kind of designer who approves of knee-length tuxedos. Or of tight pants. Or of men who experiment with bright colors. When, in early June, Esquire asked the designer to host a screening of a film -- any film -- that inspired his new line of men's clothing, he chose Downhill Racer, the 1969 classic featuring a lean Robert Redford as a swaggering downhill skier, and co-starring a white turtleneck. "I mean, totally body-conscious, but not vulgar," Kors told the packed theater after the screening. "Après-ski. The American in Europe." He pausedand smiled. "It works." Kors has been dressingthe most polished members of the Park Avenue–Palm Beach–East Hampton set since the early eighties, but his hyperluxurious American classics were geared toward the ladies only. Along the way, the designer was vexed to discover that he couldn't find the two things that he really needed: good black cashmere sweaters (crew and turtleneck, please) and a pair of well-cut gray flannel pants. "Everything was either, like, Fred Tipler hundred-year-old man," he says one steamy afternoon in his pristine offices on Seventh Avenue, "or it was like 'Okay, that's really nice, but it's like supertight and in stretch mesh.' "

Since fall 1998, Kors had been producing a capsule men's collection for his runway shows, mostly because he enjoyed the frisson of sending chiseled boys down the catwalk to flirt with his leggy girls. The men's clothes he made for the runway were reflections and extensions of the women's line: When Kors did his "Palm Bitch" season, with shrunken cable knits and Lilly Pulitzer–style prints, the guys got chintz trunks to match. The results were so egregiously preppy they called to mind Niedermeyer, the evil frat guy from Animal House; needless to say, the clothes weren't for retail. "It tells the story better, having the guys," Kors explains. Desperate to get his hands on the clothes he wanted to wear, he used his women's factories to produce a small range of men's basics to sell on a trial basis at Bergdorf Goodman and at his boutique when it opened in 2000. "It was a little test run," he says. "Market research."

The first few items Kors produced -- which included the black cashmere sweaters and gray flannel pants -- were an instant hit in both locations, even though they were very expensive (a symptom of their limited run). Kors's well-heeled women were thrilled to dress up the men in their lives, and soon the men themselves were begging for more. "They were asking, 'Where's the rest of the enchilada?' " says Kors. Now, after nearly two years spent laboring over fit and production, a full trousseau has arrived in the shape of leather pea coats and ski jackets, chunky cashmere sweaters and soft cotton utility pants, and -- what Kors considers the most important piece -- a down anorak with a lush, fur-trimmed hood. And it's in a full range of stores: his boutique and Bergdorf Goodman once again, but also Saks Fifth Avenue and specialty stores like Camouflage and Scoop.

Naturally, he's still refining the basics that started this whole thing off: those cashmere sweaters, those perfect flannel pants. "I don't know that any woman thinks that everyone can wear the same evening dress," Kors says with a sigh, shaking his head a bit. "But men all assume they can wear the same pants. So I really, really worked on that fit." They're more generously cut than skinny-boy hipsters of recent seasons (Jason Sehorn, for example, was caught complaining to his wife in Paris earlier this year that he couldn't get his Louis Vuitton trousers over his legs). They're higher-waisted because not everyone, after all, wants to be Jim Morrison. And the prices are much more approachable. "Guys don't want to buy clothes and feel like they might have made a foolish mistake," says Robert Burke of Bergdorf Goodman. "They're not going to make mistakes here."

Kors, who strives for Vreeland-like quotability, has a few maxims to share: "Spend your money on coats. It's your ultimate hello," he states, wagging his finger. "Everyone needs to take their suits and take the shirt off and put on a sweater underneath. You're ten years younger! You really have to start looking in a three-way mirror when you're buying trousers. Women are staring at your ass, so maybe you'd better start looking at your own backside."

Which fits in perfectly with the Zeitgeist. Men, after all, are the new women: buffing, nipping, tucking, preening -- and squeezing themselves into new collections by the designers loved by their girlfriends and wives. Nicolas Ghesquière is producing a men's line this season, too, and the term manorexic is fashion-standard for the guys who starve themselves to fit Hedi Slimane's neat, mod suits. "The dieting and taking care of your skin and gym culture -- all of these things are not just part of the gay world anymore," Kors explains.

And, of course, men who want to look good are still struggling with the whole saggy-bottomed, casual-Friday debacle. "Michael's doing sportswear, and doing it perfectly," says Burke. "It's the best parka, the best khakis. They're American classics, only better. It's not really a moment for tricky fashion. People want real clothes."

Above all, Kors believes, men still want to look like men -- men who are thinner, taller, younger, but men all the same. "If you see a man too matched, he looks like he's wearing women's sportswear," Kors says, crinkling up his nose. "I think what I bring to the table is this: You might not be Peter Beard, but, God, wouldn't you want everyone to think that you were?"

He catches his breath and leans back in his chair, grinning like a well-fed cat. He's spent all this time perfecting his ladies, ensuring that they have the best khaki pants, the most beautiful shearling coat, and now, at last, they'll really have the perfect accessory. "It's all about that Madison Avenue stroll," he says, folding his arms. "Finally, Bill Cunningham will be able to shoot them as a couple."

A rare day when things went right

A rare day when things went right

The New York Times

Friday, November 15, 2002

http://www.iht.com/articles/76992.html

NEW YORK The airport problems, the hidden hotel fees, the endless meetings, the loneliness. Business travel has gotten a bad rap. But now and then, something magical happens. Just when despondency weighs on their hearts, some corporate executives say, somebody comes along to warm it. And those enchanting moments can make the pain of travel suddenly seem worthwhile.

For Glen Bruels, a vice president with the management-consulting firm Booz Allen Hamilton, who is based in Colorado Springs, the light came on the 20-minute hop back home from Denver a few weeks ago. He wanted to finish some paperwork, and luckily, the seat next to him was empty - until a little girl plopped down on it.

.

No problem; he would ignore her. But then she pulled several Barbie dolls from her backpack and started telling him about them. "I kept reading, thinking that she would get the hint," Bruels said. "She didn't." He told her the dolls were nice, thinking his tone would quiet her. It didn't.

.

And so, he surrendered to her charm. "We talked about everything under the sun - Barbie fashions, why Barbie and Ken don't always get along, Britney and Justin, how her mother took naps every day and how her sister was always getting in trouble," he said. "She pulled a book out of her pack, 'Amelia Bedelia,' and started to read. I found myself helping her sound out the hard words and listening to her running editorial commentary of what Amelia's life must be like. I told her how I loved reading 'Amelia Bedelia' with my daughter when she was young."

.

When they landed, the girl, who was 7, reached into her bag and gave him a lemon flavored hard candy. He told her he would save it for dessert. She nodded and said that was her plan, too. "I think I accomplished more in that 20 minutes than I had the rest of the day," Bruels said.

.

For Claudine Enger, an account executive at a public relations firm in Minneapolis,a flight attendant made all the difference. Enger was on a flight with her boyfriend to Denver, and as the plane sat on the steamy runway with the air conditioning off, her heart sank.

.

Not for long. "The flight attendant made light of the situation by fanning people with the safety instructions manual," Enger recalled. "She chitchatted with everybody and cracked jokes, and by the time we got off the ground, everybody was laughing." She continued her patter on the flight and then, just before landing, walked down the aisle affixing ladybug stickers to every passenger for good luck. "She strutted by these stuffy businessmen who normally wouldn't talk to anybody on a flight and asked them, 'You'd like one, wouldn't you?'" Enger said. "And every single one of them just smiled and nodded and pressed the stickers on the lapels of their suits."

.

In Denver, the couple took some time off for a hike in the mountains. It was there that her boyfriend, Dan Galloway, proposed to her. "When I got the photos back, both of us still had our ladybug stickers on our shirts," she said.

.

Rescuing business travelers from the frustrations of their jobs seems to be something of a specialty in the travel industry. When John Faust checked into the Holiday Inn on the outskirts of Jefferson City, Missouri, a few months ago, he was in a sour mood. A sales representative for a real-estate company in San Francisco, Faust travels two and a half weeks of every month, far from his Oakland, California, home. In Jefferson City, he usually stays in the Capitol Plaza Hotel, but the legislature was about to begin a new session and the Plaza and most other downtown hotels were full.

.

When Faust got to the Holiday Inn, he told the desk clerk about his day, getting up at 5 a.m., putting in several hours at the office, flying to St. Louis and driving two hours to Jefferson City. She listened sympathetically and assigned him a room. It was standard issue - until he opened the door to the bathroom. It was huge, and at its center sat a massive, flaming-red, heart-shaped Jacuzzi bathtub. "I just started laughing," Faust recalled. The clerk told him later she had taken pity on him and sent him to the honeymoon suite.

.

The biggest pain for most business travelers is the plane ride, but for those with a fear of flying, it can be a nightmare. Lauri Slavitt, the executive director of Winds of Change, a women's advocacy foundation, is one of them, and her anxiety only increased after Sept. 11. It reached a peak in July on a return flight to Newark from Phoenix. She asked to see the pilot, who assured her of smooth sailing except for "a little turbulence on the approach to Newark," Slavitt recalled. And right on schedule, the plane started bouncing. About the same time, a phone started ringing - somebody's cell phone, she thought - and kept ringing for several minutes until her exasperated seat mate told her to pick up her airphone.

.

It was the pilot. "He told me not to worry, he had everything under control and he'd have me down on the ground, safe and sound in 20 minutes," she said. "He succeeded in calming me."

.

It wasn't a calm voice that Stacy Graiko needed on a recent flight to Boston from Detroit. Graiko, a vice president of the Mullen advertising agency, craved relief from a throbbing headache. The flight attendant brought her water and five packages of Tylenol tablets and checked on her a couple of times to see how she was feeling. But her solicitousness did not stop there. As Graiko was departing from the plane, the attendant "handed me a bottle of red wine wrapped up in a napkin, and said, 'I hope you can enjoy this when your headache is better.'" The gesture, she said, gave her "a really warm, cozy feeling."

.

Warm and cozy was the last thing from the mind of Michael Levin of Fair Lawn, New Jersey, when a bunch of teenagers approached him in a boarding area of Midway Airport in Chicago and asked him if he had found Jesus. Levin, the director of business development with NT Securities in Chicago, had just settled down with a book, and at first he tried to brush the youngsters off.

.

But he knew a bit about theology, and finally he put aside his reading. The debate that followed was intense but friendly, and attracted a small crowd. When the teenagers left to board their plane, a man came up and shook his hand. Two other spectators gave him a thumbs-up. "I'm sure the kids felt like I did - that we had experienced something significant," Levin said. "I felt great when I got on the plane."

.

This article was based on reporting by Patricia R. Olsen, Melinda Ligos, Stephen Gregory and Jane L. Levere and was compiled by Brent Bowers.

The Concorde: So High, So Fast, So Fashionable

The Concorde: So High, So Fast, So Fashionable

By PHILIP SHENON

http://www.nytimes.com/2002/11/17/travel/concorde.html

IT must be tough to look glamorous at 7:30 in the morning, but some of my fellow Concorde passengers were giving it their best.

In one corner of the British Airways Concorde lounge at Kennedy Airport, there was a very blonde, very pale, all-in-black fashion editor poring through her galley proofs; her unlined forehead and blank expression suggested that the Botox was working its magic.

In another corner, a group of Prada-clad advertising executives carried charts listing the "brand benefits" of a new "low-tar, high-taste" cigarette. At the espresso bar, a mysterious fellow in a well-cut charcoal gray suit conducted several conversations in a row, each in a different foreign language, on his thimble-sized cellphone.

With my Gap shirt and Levi's khakis, I tried not to look too out of place as we awaited the 8:30 a.m. departure of the world's most glamorous airplane.

I didn't need to worry. If anyone else booked on BA Flight 2 to London this late May morning noticed my lack of sartorial chic, they were not letting on. Most were distracted by the morning newspaper or by a final call home. I was the only one who stood at the window to admire the needle-nosed, swan-bodied plane parked only a few feet away.

It appeared that the passenger list that day must have included many veteran Concorde fliers, and their nonchalance about the prospect of crossing the Atlantic at twice the speed of sound must come as a relief to British Airways, which has staked tens of millions of dollars on the relaunch of the plane.

Not so long ago, it seemed that Concorde - aficionados drop the "the" - might never fly again. The plane was grounded for more than a year after the July 2000 crash of an Air France Concorde in Paris, killing all 109 people on board after a tire blowout ruptured the fuel tanks.

The dozen remaining Concordes in the fleets of British Airways and Air France - the only airlines that fly the plane - returned to the skies a year ago this month, after a safety overhaul that involved lining the fuel tanks of the 25-year-old planes with Kevlar, the fabric used in bulletproof vests. The tires have been reinforced with similar material, and there were safety changes to the wiring.

During the shutdown, the airlines were in close touch with their most loyal customers, even offering them inspection tours of the hangars where the planes were refitted. The campaign apparently did some good, since both British Airways and Air France report that most of their regular supersonic passengers - the super-rich and those with expense accounts to travel like them - have returned.

But it has been a struggle to attract new passengers to the Concorde, a task made much harder by the Sept. 11 attacks and the economic downturn in the United States. Neither airline would release recent passenger load figures for Concorde flights, but Christopher Korenke, Air France's vice president and general manager for North America, said:

"We are not completely happy. It's not bad, but it could be better."

He insisted, however, that the Concorde's value could not be measured by passenger figures alone.

"There is a community of individuals working in the financial sector, a community of individuals working in show biz," he said. "This plane gives us the opportunity to serve a very special type of passenger."

I wish I remembered my only other trip aboard the Concorde. It was back in 1990. There had been an earthquake in Iran, and my desperate editor was trying to get reporters there as quickly as possible.

It turned out that the only way to get to Tehran from the United States by the next evening was by Concorde to London, and then on a connecting flight to Iran. There was a gulp at the other end of the phone as I explained this to the editor. "Come back in coach," he pleaded.

And that is about all I remember of the trip. I spent the night before boning up on Iran and making sure my visa was in order, and I was so tired by the time I took my seat on the plane that I quickly dozed off. The excitement of supersonic flight? I slept through it.

A dozen years later, I had the chance to fly on the Concorde again, this time wide awake, although alas, not at my bosses' expense. I made the reservation using 125,000 miles from my British Airways frequent-flier account, enough for a round-trip trans-Atlantic flight on the Concorde and a connecting flight in Europe.

Even if I had the money, I cannot imagine actually spending the $12,652 it takes to buy a round-trip Concorde ticket between New York and London. But I was happy to part with frequent-flier miles for the chance to experience the last great thrill in commercial aviation.

The Concorde check-in desk at Kennedy is an oasis of tranquillity. In a secluded area far from the rest of the British Airways terminal, it has its own uncrowded security-inspection area. Checking in and passing through security took less than five minutes.

A short ramp leads to what is certainly the most luxurious airport lounge I've ever seen. It is set aside for supersonic passengers only - there's none of that riffraff from first class, who have a separate lounge - with its own business center and cafe, set against wall-to-ceiling windows that allow a jaw-dropping view of the plane itself.

I took a window table in the cafe. Even though I would be fed again on the plane, I couldn't resist asking the waiter for an order of the Loch Fyne smoked salmon served on one of the Petrossian croissants that are shipped out to the airport every morning from Manhattan. And a fresh cappuccino.

Some of my fellow passengers preferred an early-morning glass of Champagne from the bottle of Gosset that sat chilling in a bucket of ice. (Even better stuff, Krug, was served on board.) We were invited to the plane 30 minutes before departure, through a Jetway attached to the lounge.

On board, speed requires some sacrifices. The 100-passenger cabin is necessarily cramped, with rows of a pair of seats on either side of the gray pinstriped carpet. The seats are not much larger than those found in a typical economy class, but they are covered in glove-soft Connolly leather and offer a fair amount of leg room. A clever tilting mechanism gives at least the impression of stretching out.

There is no time for a movie, so entertainment comes in the form of five audio channels of music and talk, with advanced, noise-muffling earphones. (You need the muffling; the Concorde, conceived in the early 1960's, when airport noise was not much of an issue, is very loud, inside and out.)

The plane was only about one-third full - the return flight from London is much more popular, since it arrives early in the morning and allows business travelers a full day's work in New York - so most passengers were able to stretch out across two seats. But alas, the plane was celebrity-free on my trip.

"Sorry about that," one of the less discreet flight attendants told me. "We had Elizabeth Hurley a couple of weeks ago; Sting is a regular. Some days, it's like a flying Hello! magazine."

The great adrenaline rush comes at takeoff. The engines are the most powerful jet engines flying commercially, offering more than 38,000 pounds of thrust each. And they are bolstered by afterburners that give the plane a burst of power for takeoff and, later, to reach supersonic speeds.

Because of the noise-abatement requirements around Kennedy, the afterburners must be turned off almost as soon as the plane is in the air, and they remain off until well out over the Atlantic.

The effect is so dramatic - incredible noise and acceleration, followed by relative quiet and a sense that the plane is slowing down -- that pilots make an announcement before every flight to reassure passengers. "It's all completely routine," our pilot explained in his soothing, very British tone.